Barbara Freese has been thinking about the environment for nearly her entire life. As an attorney, she witnessed how the coal industry denied climate change, which led her to explore the history of humanity’s experiences in harvesting the world’s dirtiest energy source in Coal: A Human History. The book remains an ideal starting point for those new to the subject and provides texture and a unique application of many social sciences for those more well versed in coal’s past. She has a new book due out in May that spans similarly vast horizons: Industrial-Strength Denial: Eight Stories of Corporations Defending the Indefensible, from the Slave Trade to Climate Change (University of California Press). The book explore case studies from radium consumption and car safety to tobacco and the financial industry – how lucrative industries seek to extend profits at the expense of social and human progress. Energy Reporters’ Editor-in-Chief John Bowlus caught up with Barbara, from the safe distance of the internet, to discuss both of her books as well as other topics including how social psychology can help explain our relationship with coal, the environment, industry, and energy; the consequences of the 2016 U.S. presidential election; and Greta Thunberg’s moral approach to social change.

has been thinking about the environment for nearly her entire life. As an attorney, she witnessed how the coal industry denied climate change, which led her to explore the history of humanity’s experiences in harvesting the world’s dirtiest energy source in Coal: A Human History. The book remains an ideal starting point for those new to the subject and provides texture and a unique application of many social sciences for those more well versed in coal’s past. She has a new book due out in May that spans similarly vast horizons: Industrial-Strength Denial: Eight Stories of Corporations Defending the Indefensible, from the Slave Trade to Climate Change (University of California Press). The book explore case studies from radium consumption and car safety to tobacco and the financial industry – how lucrative industries seek to extend profits at the expense of social and human progress. Energy Reporters’ Editor-in-Chief John Bowlus caught up with Barbara, from the safe distance of the internet, to discuss both of her books as well as other topics including how social psychology can help explain our relationship with coal, the environment, industry, and energy; the consequences of the 2016 U.S. presidential election; and Greta Thunberg’s moral approach to social change.

1. It was a delight to read your first work, Coal, written in 2003 and revised in 2016. I’m curious what drew you to the subject then, both personally and intellectually—when environmental awareness was not what it is today—and why you focused on the human element, which was something rather new at the time, though others picked up on this approach in the 2010s, particularly in terms of oil and climate change?

I got hooked on environmental issues as a kid in the 1970s, and eventually became an environmental attorney for the state of Minnesota. Then, in the mid-1990s, I got involved in a legal case that altered the course of my life. A new law required our state utility regulators to quantify, in dollars, the environmental costs of generating electricity. Minnesota got most of its power from coal, so we focused on coal pollution, including carbon dioxide and climate change.

I got hooked on environmental issues as a kid in the 1970s, and eventually became an environmental attorney for the state of Minnesota. Then, in the mid-1990s, I got involved in a legal case that altered the course of my life. A new law required our state utility regulators to quantify, in dollars, the environmental costs of generating electricity. Minnesota got most of its power from coal, so we focused on coal pollution, including carbon dioxide and climate change.

This struck a nerve with coal interests from outside the state. They intervened and brought witnesses in to testify that we did not need to worry about climate change. It was not going to happen, they said, or if it did it we would like it, and those saying otherwise were politically motivated.

I was shocked by the scale of the climate threat and by the efforts of the coal industry to deny that threat. I became fascinated by the role that coal was playing in the world – influencing our climate, our future, and our policies – and the fact that this role was largely hidden from public view. Knowing coal had also played a huge role in our past, I started digging into the history.

The focus on the human element – both the little stories and the sweeping trends – is just a reflection of what intrigued me. If I had been an academic I might have limited myself to my own field of expertise, but I approached the book merely as someone fascinated by an important subject who wanted to explore and share it. I let myself follow my curiosity from discipline to discipline. I would unearth wonderful stories connecting coal to, say, the bubonic plague, or Mao Zedong, or J.P. Morgan, or the daily life of someone operating a kitchen coal stove. I decided that if I found these nuggets compelling then readers would too, so I wove them into my narrative.

2. If you were to tell the story of coal since your book’s publication, what would you say have been the most salient developments? What is coal’s future?

In early 2016, I published an update of the original 2003 edition, adding a chapter describing the craziness of the intervening years. We saw the power sector rush to build scores of new coal plants in the US, most of which were blocked by a growing climate protection movement and changing economics. We also saw the rise of climate protection policies, which were then largely stalled by the climate denial that took over the Republican party. We saw the coal industry achieve astonishing political power even as it was dying economically. And despite heartbreaking setbacks, we saw some encouraging progress on climate policies by the U.S. EPA and internationally, even in China.

Then came the 2016 US presidential election. If I were to write an update now, it would have to start with this president’s dangerous pro-coal rhetoric and actions — unraveling Obama-era rules, withdrawing from the Paris agreement, and promising (yet failing) to restore the coal industry. I think the future of coal right now in the US is the worst of both worlds – coal use will keep declining (hurting workers, who will be given false hopes instead of transition assistance) but not shrinking nearly as fast as it must to protect the climate. Globally, I think we are near or even past the peak of coal use, but I confess my prediction is tainted by wishful thinking (not having lately gone through the very hard work of trying to see past it). I just can’t accept the idea that humanity, having come so far, would fail this test when we have the knowledge and ability to save ourselves and our planet.

Fortunately, clean energy keeps dropping in cost, and more importantly, climate alarm and activism is reaching a new level politically. The coronavirus may help, reducing emissions while reminding us of the importance of science and government and increasing our overall sense of solidarity. (We must acknowledge, though, that it could have the opposite effect, fueling our tribalism and biases. The rise of the antiregulatory Tea Party in the US in 2010, following a financial crisis that was brought on largely by deregulation, proves that the political reaction to a crisis can be exactly the opposite of what you expect.)

When it comes to climate and energy, though, the narrative is clearly changing rapidly and the outcome of this shift will have tremendous long-term consequences. That means that energy journalism is particularly critical right now because of how it will influence that narrative.

3. You are set to publish a new book this May, Industrial-Strength Denial: Eight Stories of Corporations Defending the Indefensible, from the Slave Trade to Climate Change. Can you introduce readers to the topic and tell them what drew you to this project?

After writing Coal I went back to work as a lawyer and policy analyst fighting to stop new coal plants and to promote climate protection. This brought me again into contact with climate denial, including from people who seemed no less honest or rational than average in other respects. I started wondering again about how this kind of denial works on the mind and about how far corporate denial, as I came to call it, has affected society in the past. How far from reality has it taken us? What rationalizations did other industries use? How was this denial overcome, if it was?

After writing Coal I went back to work as a lawyer and policy analyst fighting to stop new coal plants and to promote climate protection. This brought me again into contact with climate denial, including from people who seemed no less honest or rational than average in other respects. I started wondering again about how this kind of denial works on the mind and about how far corporate denial, as I came to call it, has affected society in the past. How far from reality has it taken us? What rationalizations did other industries use? How was this denial overcome, if it was?

And so I plunged into history again, both distant and recent. I focused on eight industries that were confronted with compelling evidence that they were causing harm and who responded with long and dangerously effective campaigns of denial. As the subtitle tells you, I recount the long-ago denials of the slave trade and the modern denials of the fossil fuel industry toward climate change.

I also dig into the denials related to radium consumption, unsafe cars, leaded gasoline, ozone-destroying chemicals, tobacco, and the investment products that caused the 2008 financial crisis. These are stories of self-interested deception and delusion, but they are also stories about people outside the industries – like scientists, activists, journalists, and politicians – confronting those denials and reducing or even stopping the harm in question. It is a book about outrageous corporate behavior but also about undeniable social progress.

4. One reviewer mentioned your use of “psychological theory and insights,” which must have provided new insights to climate change. What were these, and did the climate change story resonate in particular with any of the other seven stories that you cover?

The chief insight is that none of these cases of denial can be understood by looking at the individual. They are social phenomenon, so if we want to use psychology to understand them, we must look to social psychology. That field is in flux, with some recent findings failing attempts at replication, but there is still a lot of helpful research out there.

Much of the research deals with tribalism, and how very little it takes for our brains to divide the world into us versus them in a way that alters what we perceive and believe. Studies also point to ways our perceptions of reality and feelings of responsibility are shaped by hierarchy, anonymity, power, divided labor, money, ideology, and the inadvertent nature of most corporate harms. These factors are, of course, so dominant in the corporate world that it almost seems we have designed an economy purpose-built to increase bias, reduce social responsibility, and promote denial.

All these campaigns resonate in some way with climate denial, and together they show just how extreme, sustained and dangerous this kind of financially rewarding group denial can be, even among people hailed for their clear thinking and moral fiber. And these cases show that an industry’s denial is hardly ever overcome by evidence itself. (One exception is the chemical industry finally accepting evidence of ozone depletion, though there were other factors in play as well.) We also see that even when an industry is forced to admit the obvious – like the tobacco industry finally admitting it sells an addictive and deadly product – it does not stop it from continuing to enthusiastically sell that product.

I still remain a big fan of confronting corporate denial with evidence. This is not because that evidence necessarily changes the willingness of the industry to cause the harm but because that evidence changes society’s willingness to tolerate the harm. The industry’s denial may continue, but it will be less influential. The evidence helps mobilize those outside of the industry to act, fueling a social movement, shifting the social norm, and changing the relevant policies.

5. Has Greta Thunberg helped expose industrial denial of climate change and is her model of protest effective?

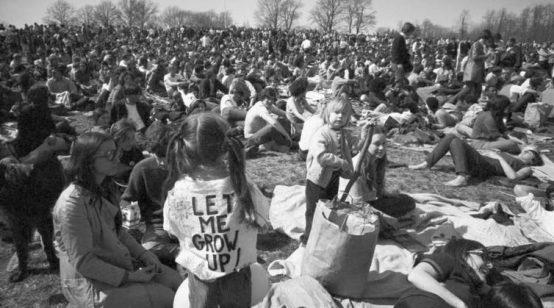

Greta Thunberg’s work really heartens me, and I think her approach is not just effective but critical. Despite what I just said about the importance of evidence, I know that the social norm does not change by evidence alone. If you tell people the building is on fire but nobody gets upset about it, then many of them will just sit there and lose their chance to escape. They will figure it could not be that bad if nobody is yelling or racing around. People need to see others with the appropriate emotional response to really feel the depth of the crisis, and Greta Thunberg is providing an entirely appropriate sense of outrage and alarm.

And Greta and the youth movement generally are framing this issue of climate change in moral terms, which is important to bring out the level of change we need at the speed we need it. Small policy changes can happen behind the scenes by evidence-driven regulators and legislators. Big social changes need big social movements, and big social movements need not just evidence but moral passion driving them.

Photo credit: pxhere.