The contours of the energy transition have grown clearer this year. Renewable energies have grown at a record pace over the past decade, but so have carbon emissions, rising 1.5% in 2017 and 2.1% in 2018. The West and its Asian allies seem to have grasped this reality, and are now betting on a source and technology that could initiate a whole scale transformation of the global energy system: hydrogen.

It is reasonable to be hopeful that the hydrogen spring is upon us. In late May, at the Clean Energy Ministerial in Canada, the United States, Canada, Japan, the Netherlands, and the European Commission launched a new hydrogen partnership coordinated by the International Energy Agency (IEA). The IEA then released a special report on the future of hydrogen during the G20 meeting in Japan in mid-June. On the sidelines of the meeting, the United States, EU and Japan then signed a trilateral agreement to cooperate on hydrogen and fuel cell technologies. There were even hydrogen bicycles available for journalists to use at the G7 meeting in France in August.

Hope in the potential of hydrogen is nothing new. The first internal combustion engine was designed in 1806 to use hydrogen. Today, hydrogen’s potential advantages are more revolutionary than ever. Pure hydrogen is clean, with water being its only by-product. Hydrogen fuel cells, meanwhile, allow us to move, store, and consume renewables on a far greater scale. They also permit the use of fossil fuels without carbon emissions. Hydrogen could even make global geopolitics less volatile. There is, in other words, something for everyone to like in hydrogen.

A European-Asian hydrogen spring

Europe and Asia are leading the hydrogen spring. Germany, the UK, and the Nordic countries have all committed major resources, while Japan made the initial push for international cooperation in 2018. South Korea, meanwhile, wants to lead the world in hydrogen, and is set to build three hydrogen-powered cities by 2022. China’s role will be pivotal, as always. No country has invested more in hydrogen to date.

The transport sector will be central to the hydrogen spring, and Asian economic powerhouses have committed to developing hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, even if China now plans to scale down subsidies for fuel cell vehicles, along with those for electric vehicles (EVs) and plug-in hybrids, in 2020. The UK government has plans, in collaboration with a California company, to build the first hydrogen-powered airplane. NASA is investing in a cryogenic hydrogen system to power its aircraft.

Even hydrocarbon lovers can embrace hydrogen. Just days after the G20, Russia announced plans to explore how it could harness its existing gas infrastructure to power hydrogen production. Saudi Arabia, who assumed G20 leadership after the meeting, inaugurated its first hydrogen fueling station that same month. The only person wholly opposed to hydrogen, it seems, is Tesla’s Elon Musk, whose battery-powered vehicles would receive stiff competition.

The development of hydrogen is following a similar trajectory as the mobile phone market did. Europe pioneered the technology with Nokia before the United States globalized the market with Apple. China and South Korea then made higher-end phones cheaper (and better, depending on whom you ask) with Huawei and Samsung, respectively. The pioneering efforts of European and Asian countries on hydrogen are essential, but will likewise require U.S. backing to go global.

Renewables not enough

Perhaps most promisingly, the hydrogen spring has the potential to blur geopolitical lines. Without hydrogen, there are two broad camps in the energy world. The OPEC+ countries and the United States want to extend the dominance of hydrocarbons. On the other side, China, Europe, and energy consumers want to increase renewables.

Hydrogen, however, allows the West and its Asian allies to compete with China, who is dominant in the production and development of renewable energy technologies, especially EVs. Battery storage limitations for renewables, interestingly, make hydrogen both a competitor to and complementary piece of boosting renewables. The hydrogen spring is, then, also a recognition that China’s massive bet on renewables is simply not enough to reverse the rising emission of carbon into our atmosphere.

Fear of China’s resource dominance is another factor accelerating the hydrogen spring. Renewables energy technologies depend on rare earth elements, and China accounts for roughly 70% of their global production. This figure was as high as 97% in 2010. China also has 50% of global reserves, while Russia has 17%, and the United States 12%. Another critical element for renewables is lithium for batteries, of which 97% of all reserves are held in four countries: Chile (57%), Australia (19%), Argentina (14%), and China (7%). Depending on four countries for our energy future violates Churchill’s enduring principle for safety and certainty in energy: diversity.

Hope over experience

Past energy transitions have involved the replacement of one dominant energy source with another. They have also occurred when a rising power was replacing an established hegemon. Britain replaced France on the back of coal’s ascendance to become the dominant energy source. The United States then replaced Britain on the back of oil.

Today’s energy transition, however, is fundamentally different in two ways: climate change is its primary driver, not a hegemonic showdown, and we live in a multipolar world. The imperative to reduce carbon emissions means that multiple energy sources – solar, wind, hydro, nuclear, biomass, hydrogen, and others – are seeking to take market share from fossil fuels. The United States also can no longer dictate the global energy regime, despite its recent bonanza in oil and gas.

The hydrogen spring is the first time I’ve felt hopeful about climate. (The last was when U.S. President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping met in Beijing in 2014 to discuss cooperation on the topic.) Nevertheless, hydrogen’s development will require serious, decades-long cooperation between world powers, which could be slowed or undone in any number of ways. Hatching the hydrogen spring reminds me of Samuel Johnson’s quip about second marriages being “a triumph of hope over experience.”

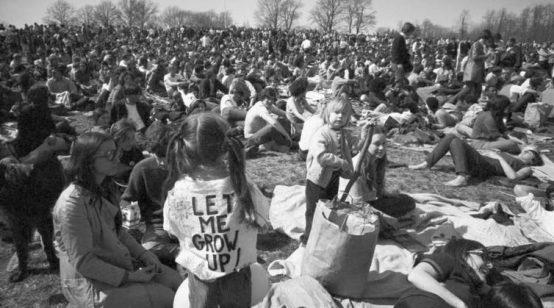

Photo credit: flickr.