A cobalt shortage could undermine attempts to bring electric cars to the market, suppliers are warning auto-manufacturers.

The silvery metal, a byproduct of copper mining, is in demand for the lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles but shortages could delay the transition to green motoring.

The bluish-grey element will be in short supply from 2025 on, according to the Joint Research Centre, the scientific advisory at the European Commission.

EU members have started to set electric-vehicle targets as part of their efforts to cut emissions.

Denmark wants to ban the sale of conventional cars after 2030 and the UK says it will only give permits to vehicles with zero emissions from 2040.

BMW spokesman Kai Zoebelein said it was “currently in negotiations with several cobalt suppliers in order to buy cobalt directly from mines” and “does not see the risk of a bottleneck in its cobalt supply chain”.

General Motors has plans for 20 all-electric models by 2023. Katie Minter, a spokeswoman for GM’s Chevrolet, said the firm was confident “based on future forecasting discussions with our suppliers”.

The Joint Research Centre report estimated that the number of electric cars worldwide would jump from 3.2 million last year to 130 million by 2030. There were around 1.8 billion registered vehicles in 2013, according to the World Health Organisation.

About 63 per cent of cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo with prices more than doubling since the end of 2016.

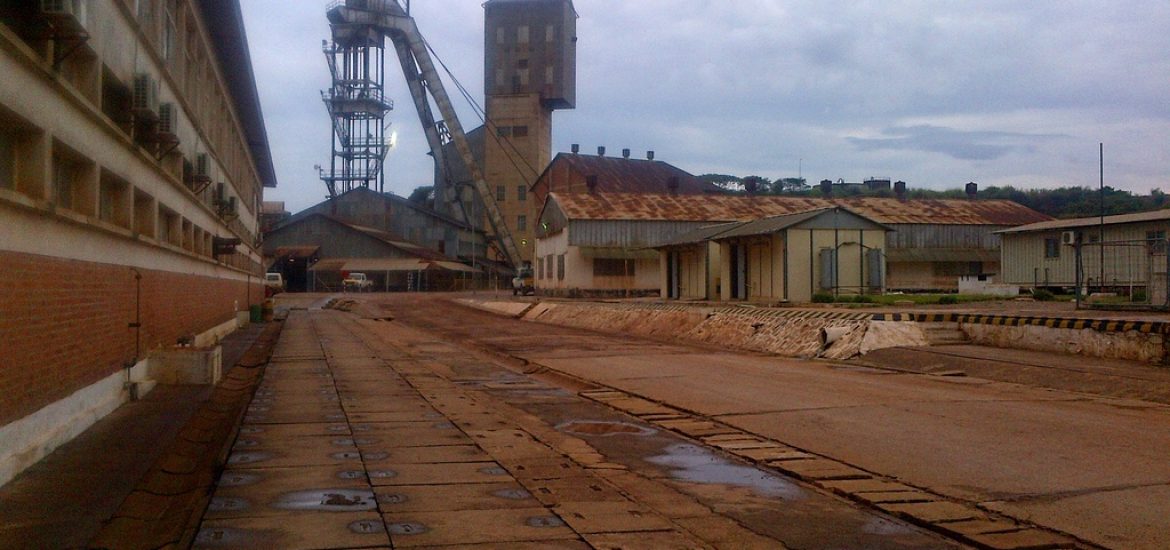

Glencore’s Katanga mine in the war-torn country was supposed to transform the cobalt market and add 11,000 tonnes to global supply this year. At an equivalent to 10 per cent of world 2017 production, it would flip the global market from shortfall to surplus.

But Katanga’s cobalt was revealed to be radioactive after uranium with “low levels of radioactivity” was found in its cobalt hydroxide product.

Katanga’s Kamoto mine produced 6,450 tonnes of cobalt in hydroxide in the first nine months of this year, seemingly on track to hit Glencore’s 2018 guidance of 11,000 tonnes before a further build to 34,000 tonnes next year.

The company says it expects to be able to process all accumulated stocks over the second half of next year.

That is assuming everything goes according to plan.

The Cobalt Institute said the global refined cobalt supply in 2017 was 116,937 tonnes with about half refined in China.

To tackle potential cobalt shortages, battery suppliers could reduce the amount used, find new sources or recycling of used batteries.

Congo’s mines have shocking human rights records. Picture credit: Flickr